Passionate about sustainable, natural living, Olmec and Melisa Sinclair have crafted a two-and-a-half-hectare oasis near Cheviot in North Canterbury. “All of the buildings were here,” explains Melisa, “but the garden was limited to a few plantings around the house, and some fruit trees.”

Having grown up on a small organic farm in the Scargill Valley, Olmec was no stranger to low impact living, however it wasn’t one he had considered pursuing in earnest until 2005.

Leaving his life in Wellington and his software engineering job behind, he set off backpacking through Australia and into South-East Asia. “For eight months I worked and travelled, gaining a firsthand perspective on other ways to live, different value systems and the nature of our expectations,” he explains. “Poor, remote villagers always seemed so happy in their simple lives and displayed an evident commitment to family, community and place.

“Over the next four years I began looking into the consequences of human settlement and our impact on our surroundings. It became evident that serious issues like species extinction, peak oil and climate change pose an enormous challenge to humanity. So I worked hard and kept my eyes peeled for a suitable location that might shelter me from the coming chaos.”

That suitable location came along in 2009, at which point Olmec and his new bride Melisa transitioned from “city-dwelling office workers to rural, self-employed lifestyle entrepreneurs,” with the aim of implementing sustainable ways of inhabiting the land and extracting a yield.

“There was no clear goal or strategy in the beginning,” shares Olmec, “we simply grew what was easy and affordable.” A “haphazard” approach that has blossomed into something truly special.

The big turning point came with their desire to capitalise on the limited North Canterbury rainfall. Radiating out from the house and offering a sense of direction through the garden are narrow contoured pathways, reminiscent of a rice paddy field. While many are simply that, a pathway from A to B, some also act as swales: depressions or ditches that follow the contours of the land to capture rainfall and help slow the process of it seeping into the soil.

“The primary objective of a swale is to intercept surface run-off that would otherwise be lost, and retain it in the landscape,” comments Olmec. “During rainfall events, once the soil is saturated, additional precipitation does not soak into the soil and instead ‘spills’ off the surface under the force of gravity and runs downhill perpendicular to the contour lines. By capturing as much water as we can, we are able to retain higher moisture levels in a drought and improve the moisture levels right across the property.

Water moves a thousand times slower through soil, than on top of the ground.”

Alongside the drive to conserve water is their desire to improve the quality of the soil and eliminate grass to improve the productivity of their eco-system. Plants that attract bees, butterflies and birds can be found within the rambling garden, while the stacking of plants such as rhubarb, fennel and mint beneath the fruit trees helps keep the grass away, eliminating the need for sprays.

For many, the thought of leaving their fennel to go to seed or the weeds to grow to waist height (or higher) might cause cold sweats; but at Blockhill they have improved the clay soil by doing just that and following a ‘chop and drop’ attitude.

“We are basically improving the soil quality by following what happens in nature,” explains Olmec. “Weeds are a large bio-mass, both above and below the ground. By cutting the plants down and leaving them where they fall, we are creating a build up of organic matter and allow the roots to retract below the surface to create channels in the soil for moisture.”

As every one per cent of organic matter in the soil enables the absorption of 15.4 liters per square metre, there are significant benefits in following such a simple notion.

This is what strikes me the most when wandering around the rambling food forest garden that is Blockhill – it is driven by simple concepts that seem achievable even to those lacking a green thumb.

“We want it to be natural,” shares Melisa. “While it’s not how nature organises itself, if we see something that wants to grow somewhere, we leave it to do so. In terms of traditional weeding, we only do this to help a plant, rather than with the aim to eliminate another.

“It is disorganised looking, but there is a method to our madness,” she laughs.

Their passion for permaculture and sustainable living is infectious and Olmec is all too happy to share what he has learned, offering consultation and design services to those looking to establish their own natural, water-smart landscape. It’s a far cry from his other love of online software solutions and web design: “I still build websites to pay the bills,” he offers.

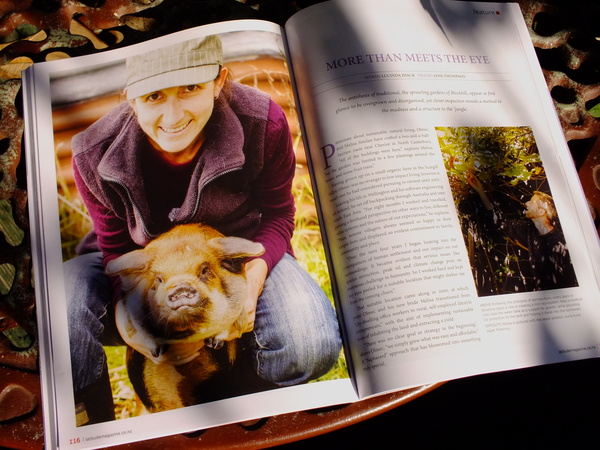

The perfect pair, Melisa is quick to point out that Olmec has the mind for the system, while her skills lie in harvesting the produce and caring for the animals, which include four kune kune pigs, four Muscovy ducks, seven hens, a rooster and two beloved cats. One of which is the inspiration behind I am Cat, a beautifully illustrated children’s book, written, illustrated and self-published by Melisa.

Describing their garden as “a food forest”, Melisa and Olmec have not only managed to create a beautiful setting but have embraced permaculture principles to achieve a natural, self-sufficient way of life.

“It isn’t about being completely sustainable,” concludes Olmec, “but about thinking about how we live and the longevity of this mindset. It is about investing in the property for generations, not just profitability.”

[ WORDS Lucinda Diack, IMAGES Jane Thompson ]